Today’s guest post is written by a dear friend that I met while living in Ecuador. On this four month anniversary of the earthquake that shattered the coast of Ecuador, I turned to Kathryn (Kathy) McCullough to ask if she would write about the relief work happening in her world view. Kathy is not only residing in Ecuador, but she is a writer and educator. Her writing is a joy to absorb, despite the difficult subject. Read on to learn about how things are progressing in a tragic set of circumstances and learn how you can help, too.

By: Kathryn McCullough

I blame a tsunami.

Following the 2004 Asian disaster that, in some cases, leveled buildings as far inland as one mile, Sara directed recovery efforts for a major international NGO. Based in Thailand, my now spouse worked in three additional countries: Indonesia, India, and Sri Lanka. But her dog Ralph remained in the US, in the same city where I lived and where I did pet sitting to supplement my meager artist-in-residence income. You get the picture. Maybe I should credit the canine with bringing us together.

Ten years later, Sara and I have lived together in several countries around the world. However, now that we’re in Ecuador and Sara is volunteering with reconstruction from the April 2016 earthquake that destroyed the homes of so many, I understand in a new way, how the international work she’s done over the past two decades has prepared her for this unique assignment.

Currently, Sara functions as a senior advisor to Proyecto Samán, part of which includes a camp that houses internally displaced Ecuadorians. A grass roots project, Samán offers a new kind of assignment for my wife, who, in the past, has worked mostly with major international NGOs, rarely with such small, community-based responses to disaster.

Sara believes that climate change will make these kinds of efforts all the more important, especially since they are rooted in local communities, rather than large, corporate-driven relief organizations bases in the US and Europe.

(You can hear Sara in this video at 3:51-5:42 and 9:14-10:33)

There’s a story Sara has been telling me for years that communicates some of the most important insights she’s gained about working across cultures, lessons she’s passed on to me. These have been remained with us when we’ve lived together overseas in places as different as Vietnam and Haiti, and, for me, when I’ve taken university students into cultures as challenging to negotiate as the Delhi slums.

Here’s Sara’s story.

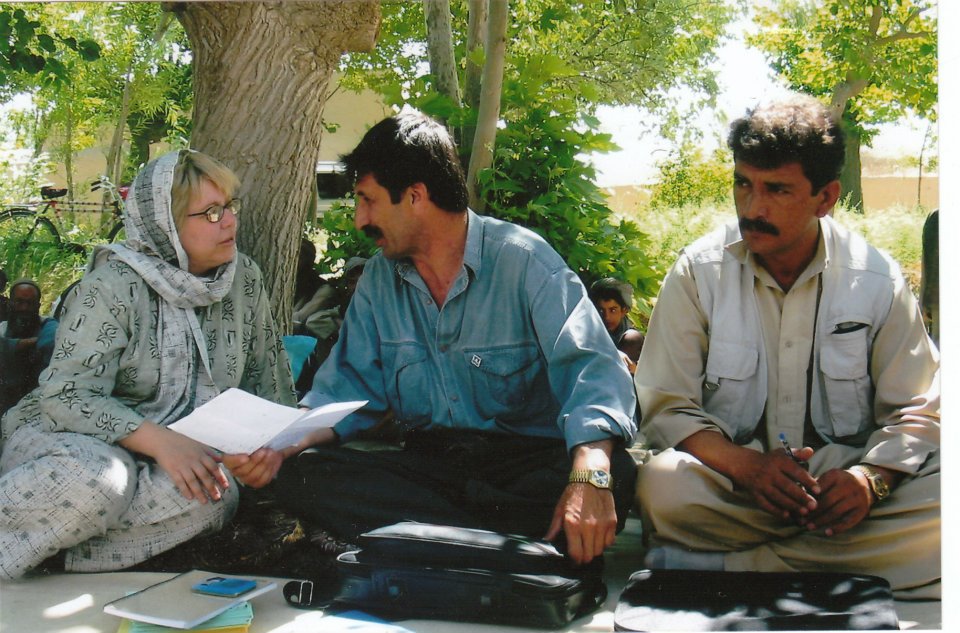

Soon after the fall of the Taliban, Sara entered Afghanistan from Uzbekistan with tens of thousands of US dollars strapped in a money belt around her waist, since then there was no real banking system in the country at that time. She was a woman alone entering a place where, only months before, women were unable to even leave their homes alone, and when they did, they were escorted to the market by male relatives and were covered in burkas.

When Sara entered Afghanistan, this kind of oppression still hung heavy in the air—a thickness.

Often Sara visited rural villages to negotiate with tribal leaders the details of reconstruction. These places looked exactly as they had more than 2000 years before. Goats and chickens roamed dusty streets whose traffic consisted of donkey carts and human feet—never of motorized vehicle. There the men’s shiny wrist watches were the only indication they were living in a modern age.

Yet when she entered these villages Sara didn’t meet with men exclusively. Whenever possible, she also made a point of visiting the women, who were still, for the most part, sequestered inside the walls of their houses.

During one walk through the narrow, village alleyways, she saw a hand motioning to her from inside a doorway—inviting her to visit, she supposed. Ultimately the middle aged woman, dressed in traditional garb, head covered, pulled Sara along and into a room where the women of the clan had organized a party for her. There was no furniture in the space, only twenty or so women, with children, sitting on hand-woven rugs, where food was spread to share with her—tea served in miss-matched cups, bowls of pomegranate seeds, sweet pastries—the very best these poor women, who lived in domed mud houses without electricity or indoor plumbing, had to offer. Playing tambourines, the group sang and danced and shared their best with her. Without a translator that day, Sara communicated with these women wordlessly—laughing, dancing, even the sharing of plates.

She says today that these women, who had next to nothing, sacrificed of themselves to share with her. Sara says she learned the meaning of true hospitality in Afghanistan and other similar settings. She came to understand that hospitality involves giving what you don’t have to give and, in the case of Afghanistan, sharing of yourself in the physical act of eating or dancing together. This, she insists, amounts to almost a sacrament of hospitality, welcoming even strangers. This is hospitality in its most genuine and organic form.

Sara also says this experience reinforced for her an insight she’s had repeated in a number of places around the world: that people living in radically different places and under circumstances profoundly unlike her own, were still more like her than not. She likes to remind me of this: that there are basic human experiences, emotions, and ways of making meaning that cross cultures. People everywhere create community by sharing food with one another. In places like Afghanistan there are no tables for serving meals. Some cultures don’t use knives and forks. Still people connect when they break bread together and in other in ways that don’t depend on shared linguistic traditions. They express delight through music and dance. They create meaning and express gratitude by giving to others what is difficult to give, by offering something that requires actual sacrifice on their part.

We encounter cultural challenges in Ecuador, as well. But emphasizing what we share with residents of any other country, rather than how we differ, allows us to create community even in the most remote places. Just as building on the strengths inherent in any local community allows them overcome disaster, so it’s helpful to recognize ways in which a country values things that we in North America and Western Europe value less than we, perhaps, should.

Sara says she eventually learned to see beyond the veils of these Afghan women—that the cloth ultimately became invisible to her—that she saw into the eyes of these women. She saw their hearts, the hand of God in a doorway gesturing to her.

Come. Share. Love.

Sara says her work itself has become a gift. She says it has become a hand in many doorways, gesturing—waving a welcome that is God, a welcome that is good.

To support Sara’s ongoing volunteer work on the coast of Ecuador, please click here.

Sara Coppler: An architect by training, Sara began her work in poverty housing more than twenty years ago, volunteering locally for an NGO that today works in more than 100 countries. Later, during the 1990s, she directed a national project in the southern US, rebuilding churches destroyed in hate-related arson. She was one of the early international aid workers to enter Afghanistan following the fall of the Taliban in 2002 and directed the rebuilding effort of the same INGO in India, Indonesia, Thailand, and Sri Lanka in the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami. More recently she spent a year in Vietnam, before directing the housing recovery project for the same organization, when the 2010 earthquake left a million and half Haitians homeless. Currently she volunteers as a Senior Advisor to Proyecto Samán, near Canoa, Ecuador.

Sara Coppler: An architect by training, Sara began her work in poverty housing more than twenty years ago, volunteering locally for an NGO that today works in more than 100 countries. Later, during the 1990s, she directed a national project in the southern US, rebuilding churches destroyed in hate-related arson. She was one of the early international aid workers to enter Afghanistan following the fall of the Taliban in 2002 and directed the rebuilding effort of the same INGO in India, Indonesia, Thailand, and Sri Lanka in the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami. More recently she spent a year in Vietnam, before directing the housing recovery project for the same organization, when the 2010 earthquake left a million and half Haitians homeless. Currently she volunteers as a Senior Advisor to Proyecto Samán, near Canoa, Ecuador.

Kathryn McCullough: Kathryn is an author and artist who divides her time between coastal Ecuador, where her wife volunteers, and the highlands of Ecuador’s Andes, where she writes and enjoys the cultural richness of Cuenca, a city whose colonial center is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Kathryn comes to writing as a former academic, who has taught compositions at several universities in the US. She writes periodically for the Huffington Post and blogs at Kathryn Reinvents. She is working on a memoir called “Kids Make the Best Bookies,” about growing up in a Pittsburgh, organized crime family.

Kathryn McCullough: Kathryn is an author and artist who divides her time between coastal Ecuador, where her wife volunteers, and the highlands of Ecuador’s Andes, where she writes and enjoys the cultural richness of Cuenca, a city whose colonial center is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Kathryn comes to writing as a former academic, who has taught compositions at several universities in the US. She writes periodically for the Huffington Post and blogs at Kathryn Reinvents. She is working on a memoir called “Kids Make the Best Bookies,” about growing up in a Pittsburgh, organized crime family.

I absolutely love the depth and heart of this piece. I know Sara, and she *is* a true Sheroe. Everyone in the Saman Project is the Divine Hand in action. I love the way you write about your wife. Thank you, Kathryn.