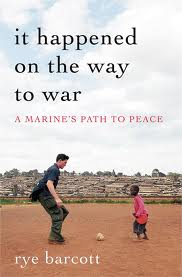

Moving to North Carolina has created some unexpected opportunities. I have crossed paths with author Rye Barcott three times over the past two years and this past time I was able to grab him for a quick interview. Rye’s story is incredibly compelling and entirely too complex for me to describe in a blog post. The short version is that Rye served in the Marines and co-founded Carolina for Kibera (Kenya). He wrote about his experiences serving in both capacities in a brilliant book called “It Happened on the Way to War.” Our conversation focused on re-entry, which is especially complex when one returns from war.

(If you haven’t heard of Rye Barcott yet, please don’t fret. NAFSA’s national conference in St. Louis will be featuring him as a speaker. I cannot emphasize enough how important that it is that you attend if you’ll be in St. Louis! You’ll walk away with a new perspective on the military, service, volunteer abroad and re-entry.)

Here is an excerpt of the conversation that Rye and I had in a busy little coffee shop on a very rainy day in Winston Salem, North Carolina last year. We spoke about the art of coming home from war while also serving as co-founder of an NGO in one of the largest slums in the world in Kibera, Kenya. This is where I hit the record button:

RB: With time you have some ribbons on your chest. Napoleon once said it’s amazing how many people will give their lives for a tiny piece of ribbon. So the ribbons are respected, but they also tell a story and show where somebody’s been over time. The positive attribute of that is that it reinforces the culture of doing and serving. The largest source of post traumatic stress syndrome is not seen as devastation or losing people that you know. It is the regret from the decisions that you made that you can’t go back by and if you don’t have some way of processing that preferably with some person, then it becomes an albatross and you live with it for decades of time and that’s part of what many still go through. That’s one of the reasons why, you know, therapy can be such an effective tool for folks. I mean, I was fortunate because I had graduate school and I had my mom (to discuss this with).

Melibee: Your mom was an anthropologist, right?

RB: Yes, my mom’s an anthropologist. I had my wife who’s a psychologist. And I also had all these people I trusted kind of gradually helped me get there by saying things in ways that I could hear because if you don’t there’s a moment where you have to go gradual and really be you know, thoughtful and deliberate with it. That’s why the word that you’re embarking on (re-entry) is actually having a structured period of reflection with some concrete objectives and outcomes from this experience is really vital for actually having it mean something. The quote that you hear ad nauseum from some of these study abroad programs is that it will change your perspective forever; I don’t think that that will necessarily happen unless the person finds a deliberate way to reflect on it and find meaning from it and that doesn’t, it doesn’t just happen on face value.

Melibee: And I think it’s just that feeling of being misunderstood, unless you have that ability to process it with other people who understand it to some extent.

RB: Yeah, and your peers are not necessarily the best….it’s helpful to have a support network for when you’re traveling for the first time and if you’re traveling in a group of five folks but, if all of them are also traveling to the same place and having a shared experience it’s very, very useful that somebody has helped them process it thats outside of that group and asking you the kind of questions that you wouldn’t necessarily ask yourself.

Melibee: Would you say that your experience returning from Kibera and your experience returning from the war were similar in that sort of trauma – that post traumatic stress syndrome – or do you feel that they were different?

RB: They were different because frankly the stakes were higher in combat for me because I was directly responsible. You know, one of the nice things about participatory development (regarding Kibera) is that it offers an escape. Somebody asks what your strategy is for the organization; my response is “That’s gotta be determined by the ground.” Somebody asks what’s the long term view of this, how does the organization sustain itself? I respond, “Well, our team on the ground needs to figure that out and I’m here to support it and I have some ideas on it but it’s not my responsibility,” whereas when you’re twenty-two years old and you’re a first lieutenant in the Marines, every life is your responsibility. And if one of your men doesn’t come back, God forbid, you are the one that’s answering for it and you are the one that has to write the letter to their parents, that mother….

Melibee: It is hard for me to even imagine trying to process.

RB: Were you there when I told the story about the ….

Melibee: mother?

RB: (Rye had told a story that day about how he was included in a group of veterans who were pulled on stage at the Democratic National Convention in Charlotte, NC, USA). Yeah, it was an amazing moment at the DNC with this video with a stunning poem that a mother wrote about a deceased soldier. Right when she concludes, the lights came up and we were on stage. The lights in the convention center turned on and everybody in the room held out the signs that we didn’t know they were going to do, and the signs said “thank you.”

Melibee: When you left the military, when you were preparing to leave the military, did they have any sort of program to help you think about how to process it?

RB: No….I mean at that time, it wasn’t done. We were still a mess with all of this; I think we are getting better now but it wasn’t.

Melibee: (Speaking about Beyond Abroad: Innovative Re-Entry Exercises) One of the exercises is about using different audiences to understand how you can get that elevator speech for re-entry down. We suggest practicing it with different people in mind, for example how would the re-entry elevator speech change if I’m talking to you versus talking to a colleague versus talking to a friend’s mom…you have to process the experiences abroad to understand what it all means. So the military didn’t do that with you?

RB: No. I mean on that note, I try to emphasize in the book without showing and not telling that…you should feel guilt, I mean you should feel some sense of guilt that as a student you are there (he is referencing Kibera’s volunteer abroad experience), you are participating, if you are going to a hard place that’s wrapped by cycles of violence and poverty that you’re going there, you’re getting the learning experience and then there’s really nothing else that tangibly comes from your participation. But, you have to have a way of actually making sense of it and wrestling with it in a group or structured program helps with that. The guilt itself is something that’s healthy only if you acknowledge it and think through it – how am I going to make that matter and carry it forward in some way?

Melibee: When you think of the people who are serving in Kibera now, the American students, or international students that are going to the University of North Carolina (partners in Carolina for Kibera), what lessons do you observe about re-entry? What do they teach you, touching back to their lives and the program’s life? What are you reminded of?

RB: The biggest lessons we learned tactically was that we just don’t have the capacity to handle large numbers of volunteers – it’s not good for them, it’s not good for the organization, so we do very small numbers. It’s not written commitment but it’s an expressed, verbal commitment that they will continue to volunteer with the organization for at least a year afterwards. Many of them volunteer ten years afterwards and so that’s a way that we kind of keep them engaged. We work with them beforehand to really structure exactly what it is that they’re going to be doing and why and make sure that’s clear to them as well as the team on the ground, and those are all the lessons that I learned over the course of the decade. The other piece on that is just a piece of advice for students I think, which is, there’s no shortage of things to care about so find one and commit yourself to it, and when you’re studying abroad there are multiple different ways of doing it. You can try and go to every continent, go to many continents as you want but if you really want to make an impact in the places you go, and if you don’t then that’s fine, but make it a deliberate decision, but if you want to make an impact in a place you have to commit over a long period of time; that means going back, that means, you know, passing on the spring break to Mexico to go back and keep those relationships fresh and healthy.

Rye Barcott will be speaking at NAFSA on Thursday, May 30th. I’d recommend that you grab his book ahead of time and read more of his wisdom prior to hearing him present live. His incredible story of how Carolina in Kibera was founded will move you to tears. It is particularly jarring in that is happened WHILE Rye was serving in the Marines. Now that’s service – redefined.

(Heading to the NAFSA conference? Join us on May 10th for this exclusive session on conference tips!)

Before you travel how much studying do you do on that place? Are you ever afraid you just cant adapt to the new culture?

I can’t speak for Rye, but I can say that I read up as much as time permits before I travel. I usually connect through my own network with locals prior to departure whenever possible. Do I worry I won’t adapt – not at all. I see it all as part of the great experience of traveling – every moment is a learning and reflective experience. 🙂 Thanks again for writing!